A framework for IT controls

Author: Dean Sleigh

Businesses are becoming increasing reliant on IT to drive shareholder value and streamline business activities. While using IT presents a number of opportunities to a business, it is not without its problems.

In recent times, there have been a number of spectacular IT system failures. Amazingly, these have been more common or more widely published in industries that place a high degree of reliance on IT to conduct their business. Examples include an airline’s booking system that was down for 11 days, causing a $15–$20 million impact on pre-tax profit, and let’s not forget the numerous bank payment and ATM system failures that have occurred over the last 12 months.

No doubt the majority of these entities impacted by IT failures had lofty statements in their annual reports and on their websites outlining the detailed framework in place to identify and treat the risks of the organisation. The reality is that rhetoric is the poor cousin to action.

How did these problems occur? The simple answer is poor IT controls.

The extent of these and other IT failings has impacted the ability of corporations to conduct business, maintain credibility and satisfy customer needs.

These system failings also raise the question as to how management and directors can be assured that their IT systems and applications are robust and can withstand both internal and external stresses.

For entities operating in highly regulated sectors, such as gaming, significant focus exists to ensure that such IT failures do not occur, because if they do it could be disastrous for the operations of the business. Often for these companies, one factor that impacts their licence is the adequate operation and reliability of their IT systems.

Is there a silver bullet to prevent IT failures? The answer is “no”. What is required is a commonsense approach with the right people focusing on the right things.

One element that is critical for success is a well-resourced and capable internal audit function. Also, simple testing and review go a long way in telling a story and providing some real answers. However, it is more often the case that the resources given to the internal audit team and their capability are not sufficient. The consequence of this is that the internal audit function fails to gain the necessary depth and coverage in its work to provide the assurance that stakeholders demand.

What coverage is adequate and what should the role of internal audit be? Also, how can management help bridge the gap if internal audit resources are fully committed on other activities?

The role of internal audit

An appropriately resourced internal audit team should have an annual audit plan that requires all major risks to be considered.

Latent in this is the need to review IT applications and key elements of IT infrastructure. In relation to IT applications, a high-performing internal audit team should be resourced and capable of conducting IT general controls (IT GC) testing against each and every critical IT application that the organisation relies upon to operate the business.

For nimble organisations, this population will be relatively small — perhaps up to 20 applications. For large diverse organisations with multiple lines of business, it would not be uncommon to have more than 100 applications (or separate instances) used across the business.

The scope of IT GC is not new and has been well defined over time. What is new is the risk associated with individual system failure and the growing proliferation of systems across organisations. The audit response needs to keep pace with this growth while not seeking to review each and every application. The risk of failure of a particular application needs to be assessed in order to determine the specific IT applications to be focused on.

Table 1 provides a simple summary of the scope of IT GC:

| Basic IT controls | Extended IT controls (examples) |

|---|---|

Security and access

Change management

Computer operations

|

Performance and capacity Service desk and incident management Data management Third-party services IT continuity |

While Table 1 might suggest that a large amount of work is involved, for a well organised IT audit team the extent of testing and disruption to management is far less than you would think. Based upon our experience, we estimate that each application should take less than 10 days to test — hardly an onerous commitment when considered against the possible cost to the business if one of these applications fails.

Management (both business and IT management) should easily be able to provide the evidence that is required to pass IT GC. It should be working to a standard well above basic IT GC compliance. Often, while management says it is doing this, testing reveals otherwise.

Experience indicates that the most common areas of weakness when testing IT GC are:

- systems access (password configuration and lack of user access reviews);

- change and release management controls; and

- backup and recovery processes.

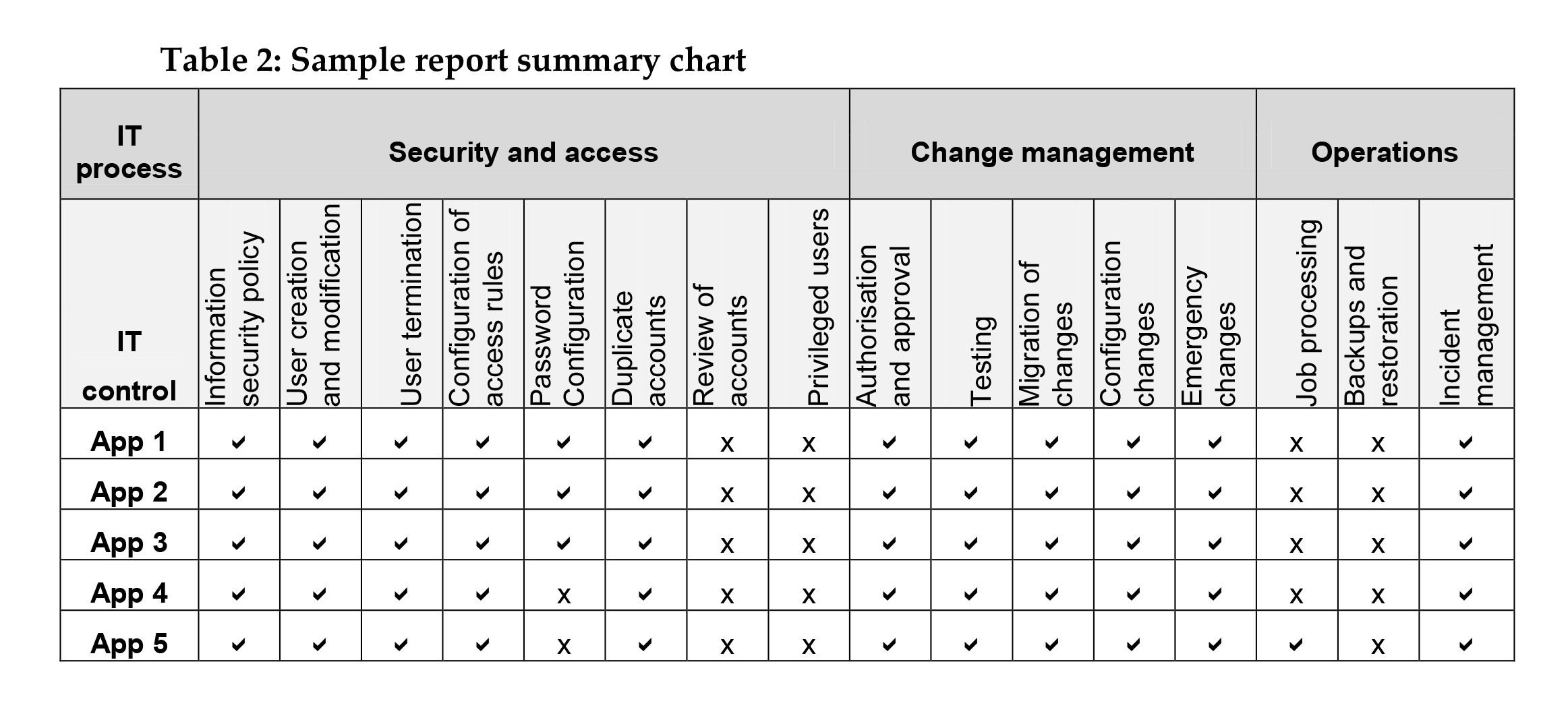

It is also common to find issues relating to the maturity of processes for availability and capacity management, patching and virus management. Regrettably, the ability of many IT audit teams to clearly articulate these weaknesses is compromised through reports that are overly technical and/or complex. In our experience, a simple summary chart outlining pass or fail criteria is a more effective way to present findings to management. An example is depicted in Table 2.

How can management help bridge the gap?

Management has far greater knowledge and intimacy regarding the systems than does the IT audit team. Management also has prime responsibility for ensuring that the risk appetite is being satisfied as it applies to IT applications. The first contribution management can make is to recognise the need for IT GC to be the minimum standard. Building and enforcing policies to ensure that IT GC is met is a tangible way of demonstrating such commitment.

In simple environments, this can be easily achieved. In complex environments with multiple applications and often large elements outsourced, this requires active engagement and clear expectation setting with the outsource providers.

Many organisations outsource some part of their IT operations to third-party providers and rely on Statement of Auditing Standards No 70 (SAS 70) reports to provide assurance over IT controls for the outsourced services. The passive receipt of SAS 70 style comfort letters is often insufficient, as these are often unclear regarding:

- exactly what was tested — the controls selected and the extent of testing for the control objective may be insufficient to provide the level of assurance required and

- scope and coverage — SAS 70 reports often cover multiple organisations and therefore it is important to understand if the same level of controls is applied by the third-party provider over your organisation’s IT systems.

The second contribution management can make is to actively expect relevant members in management teams to accept that they have a role to play in IT GC. This emphasis can be used to push down the importance of IT GC to those best placed to ensure it is met, and gives those team members the opportunity to spend the time required to ensure it is met. Many IT organisations have adopted elements of the COBIT maturity model-1 to assess the current state and define the target maturity level for IT controls. COBIT also provides a common language and can be mapped to international standards such as ITIL and ISO 27000.

Management (both business and IT management) should easily be able to provide the evidence that is required to pass IT GC. It should be working to a standard well above basic IT GC compliance. Often, while management says it is doing this, testing reveals otherwise.

When properly articulated, we have not seen a business owner argue against IT GC as being important!

Experience indicates that the most common areas of weakness when testing IT GC are:

The third thing management can do to support broader adoption of IT GC across the organisation is to reduce the expectation on external audit. The focus of external audit is on the financial statements. This responsibility will rarely extend to testing for IT GC across every major application; it may only extend to testing the key financial systems, and even this is not always clear. Reliance on external audit in relation to broad IT GC assurance is not wise.

The last thing management can do to support an improved environment is to advocate that internal audit has a comprehensive program of work to review IT GC for each material application. This advocacy may require a long-term commitment, but the rewards via a better-controlled environment and broader understanding of IT GC across the business will be well worth the effort.

Conclusion

As we increase our reliance on IT applications to execute everyday transactions, it is critical that we continue to evolve the control environment of the organisation. The rapid growth in customer-facing and customer-impacting applications is actually making the IT environment more complex and fragile.

To support managing these risks better, management needs to recognise the need to meet minimum control standards and internal audit needs to develop agile but comprehensive testing approaches covering all major applications.

1 COBIT is an IT governance framework and supporting toolset created by the Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA); see www.isaca.org